Frida Kahlo: From 20th Century Artist to 21st Century Feminist Icon

Frida with Olmec Figurine, by Nickolas Murray, 1939, Coyoaćan, Mexico © Nickolas Murray Photo Archives

When considering the theme of this month’s issue and how the idea of a “cultural touchstone” could apply to art, various possibilities emerged. Perhaps a cultural touchstone could be a single artwork, such as Michelangelo’s David (1504), Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), or the more recent Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998). These works are all extremely well known and could even be described as “famous,” and they have had a lasting influence on the development of art since they were created. Such works are often so groundbreaking or popular that they are used as a touchstone to compare later works. However, a cultural touchstone can also be a cultural phenomenon that links generations within a society. It is therefore possible that an artist, who has received widespread recognition and “fame,” even posthumously, as in the case of Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), could also be explored in regards to this theme.

Frida Kahlo was a 20th century Mexican painter known particularly for her self-portraits. The perception of Kahlo and her art has changed dramatically from during her lifetime in comparison to the present day. In recent years, Kahlo has become somewhat of a feminist icon, inspiring 21st century feminists across the world, largely due to the her successful career and the challenges she overcame throughout her life. Since her death in 1954, Kahlo has become an artist whose recognition and praise has moved beyond the art world and into the mainstream, contributing to the current perception of her. She is one of the few women artists to have achieved this level of recognition due to a canon (art historical term for artists or artworks perceived as having a certain “genius” and talent) of predominantly white, middle class men who are revered as “the best” artists. The current perception of Kahlo as a feminist icon is an interesting one because it places a modern version of feminism as an ideology onto a figure from the past. It is unclear if Kahlo herself would have identified as a feminist, or the equivalent for the first half of the 20th century, but when analysing her art and life, it becomes clear why she is perceived in this manner today.

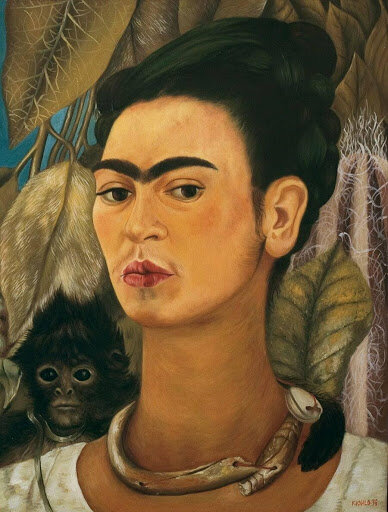

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, oil on canvas, The University of Austin, Texas, USA, © Bank of Mexico, Fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust

Kahlo’s paintings draw from an array of sources of inspiration, such as Mexican folklore and the Surrealist movement. They often engage with the fragility and vulnerability of life through themes of the body, particularly in her self-portraits, such as birth, life, and death. Kahlo’s painting Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) depicts Kahlo herself staring back at the viewer with a strong and resilient appearance. She wears a necklace made of thorns and it is sometimes suggested that this necklace alludes to Christ’s crown of thorns. It is an example of her work that deals with not only the vulnerability, but also resilience of the human body and mind. The imagery of the hummingbird that hangs from her necklace and the monkey and black cat that surround her shoulders have been said to each have symbolic meanings from ancient Aztec and in Mexican folklore. The work also references the visual language associated with Surrealism, and Kahlo is sometimes even referred to as a Surrealist (a movement that developed in the 1920s with the goal to express the unconscious through art). However, Kahlo denied the notion that she was a Surrealist, stating, “They thought I was a Surrealist but I wasn’t – I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality” (‘Mexican Autobiography’, TIME Magazine, April 27 1953, 92). Kahlo’s own reality was something she wrestled with in her works, and in addition to her skilled paintings, it is arguably a reason for her position as a feminist icon.

Frida Kahlo, Two Fridas, 1939, oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City, Mexico, © Bank of Mexico, Fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust

This is largely due to the challenges she overcame throughout her lifetime. Kahlo had multiple health issues over her life, including a severe bus accident that left her with serious injuries and confined to bed for months. It was during this time she began to paint, and many of her works reference how she saw herself and her body during this time, such as The Broken Column (1944). In addition to constantly battling health issues and developing a successful art career, Kahlo was very political, and a member of the Mexican Communist Party for a time. She is also known for embracing both feminine and masculine elements in her style, in a way that was unapologetic and has inspired and liberated generations of women since. These factors have led to her current status as a feminist icon, but it is often the image of Kahlo as opposed to her artwork that is recognised and used today.

This is likely because Kahlo’s image and her art are so intrinsically linked due to her self-portraits and the personal subject matter she explores in them. She took great care in how she presented herself for photographs and in her art, leading to a curated image of her signature monobrow, floral headdresses, pre-Columbian Jewelry, and often Mexican Tehuana clothing to become so recognisable. In 2018, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s largely popular exhibition, Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, presented a collection of personal items and clothing that belonged to Kahlo. Many of these can also be viewed at The Museum of Frida Kahlo, or Casa Azul, in Mexico City – her old home which became a museum in 1958. While the V&A exhibition did display some of her paintings, the focus was placed on her personal items and particularly her clothing. This biographical way of exploring an artist is not uncommon, and many blockbuster exhibitions and books written about Kahlo follow this monographic format. However, in Kahlo’s case, she is so often referred to alongside her husband, artist Diego Rivera (1886 – 1957), and their turbulent relationship. It is important to be careful not to rely on biographical details at the detriment to the artist and their work.

Kahlo’s unapologetic and resilient approach to life and what she has come to stand for has led to the development of her status as feminist icon. Her recognisable image is used in many forms and can repeatedly be found on numerous objects such as art products; household items like plant holders and mugs; make-up brushes; and printed t-shirts (and now even face coverings). While this is an understandable and fun way of celebrating a figure that is an inspiration to many, we must not forget to appreciate Kahlo as a significant 20th century artist who contributed to the language of modern art. Frida Kahlo’s biographical details and recognisable signature image are what come to mind for many. However, her rightful status as a feminist icon would not have developed if not for the poignant themes explored in her work of self image and the fragility of human life in a way that has continued to resonate with society over the years, and has led to the perception of Kahlo as a great artist.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkey, 1938, oil on masonite, Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, New York, USA, © Bank of Mexico, Fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust

Sarah McDermott Brown is a graduate of the University of Birmingham with a BA degree in History of Art and a MA degree in History of Art and Curating.